|

When most people finish a five-year run of accolades and All-American

status, they take a little time off to reflect on what they have

accomplished, but not Lily Kahumoku.

Instead, two weeks after a

disappointing loss to Florida in the Final Four, she hopped on a plane to

spend her winter in Siberia. Yes, that Siberia, of the gulags and Arctic

winter fame.

“ It’s minus 20 outside, and it is like putting your face

into a hot oven,” says Kahumoku, now safely back in our Islands since

March 20. “You inhale the air and it burns your teeth, like biting into an

ice cream.”

So how does a native Hawaiian from Texas end up in

Khabarovsk, a town 500 miles northwest of Sapporo on the Chinese border?

It dates back to a 2002 exhibition match with the Russian club team

Samorodok. The Wahine crushed them — with Kahumoku leading the way with 26

kills — and the coveting began.

Once Kahumoku’s and fellow Wahine

Lauren Duggins’ college eligibility had expired, the Russian Gold-Mining

Company AMUR, which owns Samorodok, came with offers they couldn’t refuse.

“ I was treated like a goddess,” says Kahumoku in the soft

tones of a child whispering secrets in the back of the class. “We stayed

in a three bedroom luxury suite, they took care of our meals, taxis and

gave us the newest technology in winter clothes.” “ I was treated like a goddess,” says Kahumoku in the soft

tones of a child whispering secrets in the back of the class. “We stayed

in a three bedroom luxury suite, they took care of our meals, taxis and

gave us the newest technology in winter clothes.”

This is not to

mention her salary that she declined to reveal, saying only that they took

very, very good care of her. Despite the royal treatment, her partner

Duggins lasted less than a month before packing for home, and Kahumoku

found herself longing for the Islands herself.

“ I cannot picture a

place more consummately different from Hawaii,” says Kahumoku, shaking her

head as she struggles for the words to capture it. “It was like a dream,

so surreal, like it wasn’t real, like The Matrix.”

She isn’t just

talking about the weather. While elegant, she found caviar for breakfast

each morning delicious, but not something she wanted every day. The

ubiquitousness of beets in the diet and the daily serving of borscht

(“Portuguese soup gone Russian”) had her wishing for a plate lunch.

Also, with her only English speaking ally gone, she had to learn

Russian on the fly.

“ It is so different from the Hawaiian language that has a lot of

vowels. There you have three, four, even five consonant sounds in a row

and it’s like, wow,” says Kahumoku before letting loose with a series of

Russian words to demonstrate.

She learned the language by watching

American movies dubbed into Russian, and while not fluent, she could

survive and, more importantly, play volleyball.

“ The language barrier

was the toughest thing; I didn’t know if my teammates are plotting my

death or want to be my best friend,” says Kahumoku. “You just don’t know

because they are so stoic. But now, I can’t speak English while playing

volleyball!”

Despite making loose connections with her team, there are

larger issues with the public as a whole in the post-USSR era of Eastern

Siberia.

“ There is a very strong anti-American sentiment in Russia

and it is very hard to get past that,” say Kahumoku.

But there is one

way to get past all prejudices, and that is to perform. Volleyball is the

second-largest women’s sport in Russia, attracting up to 6,000 fans to her

home games on the Amur River. All the games are televised, and with

winning comes acceptance.

“ It was so weird,” says Kahumoku, “people

would come up to me on the street and say, ‘We love your team, and we like

your play.’”

These accolades came with good reason. She took a

little-regarded Samorodok team and led them to a top 5 finish — their

first-ever — and assured them a spot in the Super League next season.

For this and her plus .500 kill percentage, she was awarded the first

Master of Sporta ever given to a foreign player. It is our equivalent of

All-Pro and something she will always cherish, even if she cannot spell

the award in the Russian crylic alphabet.

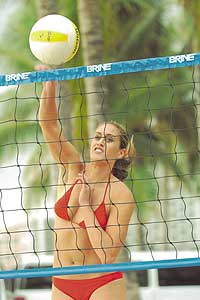

Taking the monetary earnings

and experience (“I went there pudding, now I’m jerky”) she is taking her

act to the AVP, America’s professional beach volleyball circuit.

“

Part of the reason I went to Russia was to make money to pay for (AVP

Tour),” says Kahumoku, who has to pay for her own travel and lodging until

she garners some sponsors. “Ever since I was a little girl my dream was to

play beach volleyball with my older (half) sister, and now it’s coming

true.”

Her older sister is Jessica Alvarado-Brannan, star of the Long

Beach State team that went 36-0 in winning the National Championship in

1998, and now two-year veteran of the AVP tour.

The teaming seems

perfect with Kahumoku’s powerful style from the left and Alvarado’s ball

handling skills and passing on the right. Only problem, the two of them

have never played together and won’t have a chance to before their first

event April 23-25 in Tempe, Ariz.

Also the differences between a power

six-person indoor game and the finesse and stamina of the beach sport

could provide hurdles, but Kahumoku pooh-poohs such talk.

“ It’s not

going to be hard; our style is so similar and we talk so much, I don’t

think training together is that important right now,” say Kahumoku, who

plans on residing here in the Islands and finishing her degree at UH while

flying in for events.

Her professional career lies ahead of her, ripe

with the potential to become the next Gabrielle Reece, and poised to

represent the United States in the 2008 Olympics. If all goes well in the

AVP, look for her to be playing in the Hawaiian Invitational at Fort

DeRussy Sept. 23-25.

But even with her world travels and golden road

ahead, she still remembers those who brought her here.

“ By far,

Hawaii fans are the greatest in the world,” says Kahumoku, who tells of

Russian fans who, while exuberant, would throw bottle caps and rubbish at

them on the court. “I don’t think there is any other place that

appreciates women’s volleyball (like Hawaii) and really embraces the

sport, and I am so thankful for having that experience.”

|